Thoughts on Contrastive Representation Learning

This passage initiates by addressing the question depicted in fig.1 text. Despite reviewing the referenced papers [1-6], I acknowledge lingering uncertainties regarding the nuances of contrastive representation learning. Therefore, I draft this for later review and reflections.

Recent approaches utilize data augmentations as weak supervision to distinguish retained information, termed ”content”, from discarded information, termed “style” [2]. However, the agreement on real-world data generation process, particularly the identifiability of true causal relations in data generative mechanisms, currently lacks consensus.This lack of agreement introduces uncertainty around terminologies like ”content” and ”style”, and their distinct definitions hinge on how we conceptualize them and how we set the learning objective. Nevertheless, this issue seems to be primarily a matter of nomenclature. The resolution of this uncertainty is anticipated to come with consensus on the identifiability of true mechanisms of data generative process.

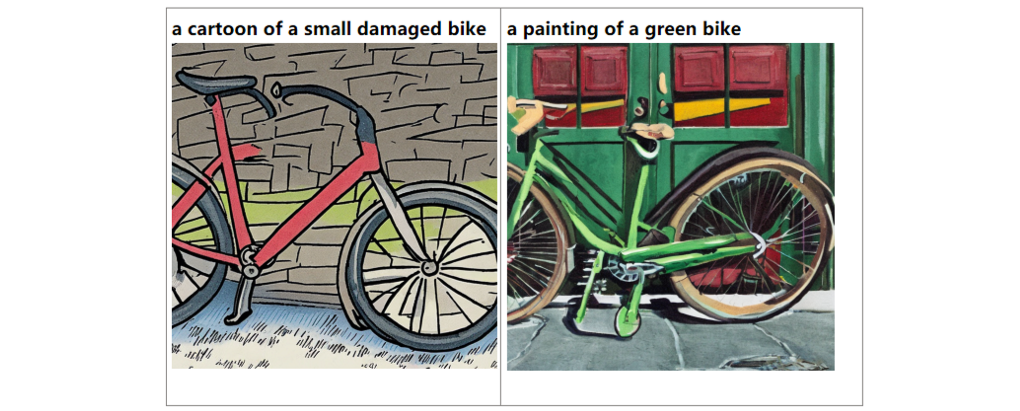

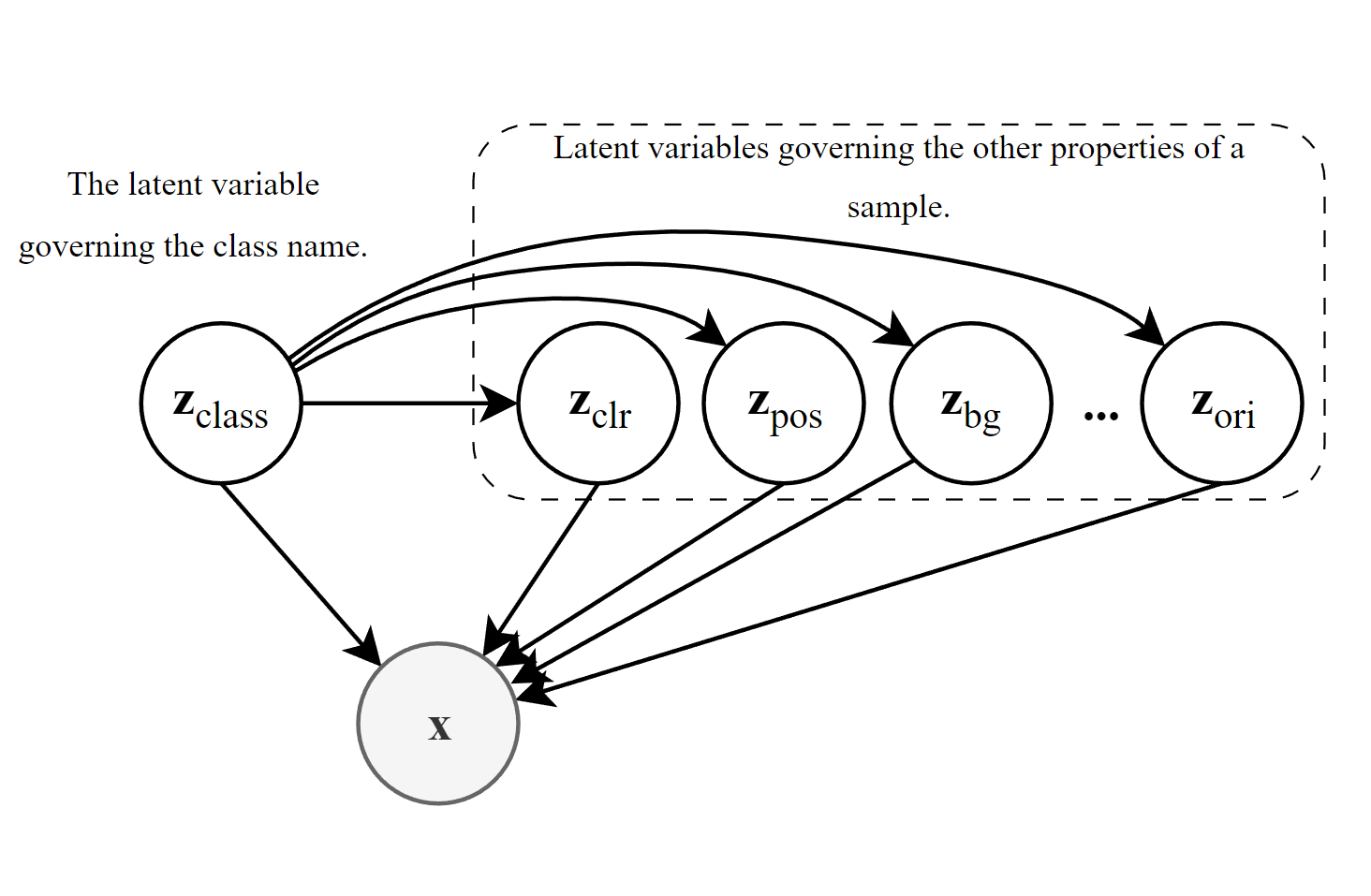

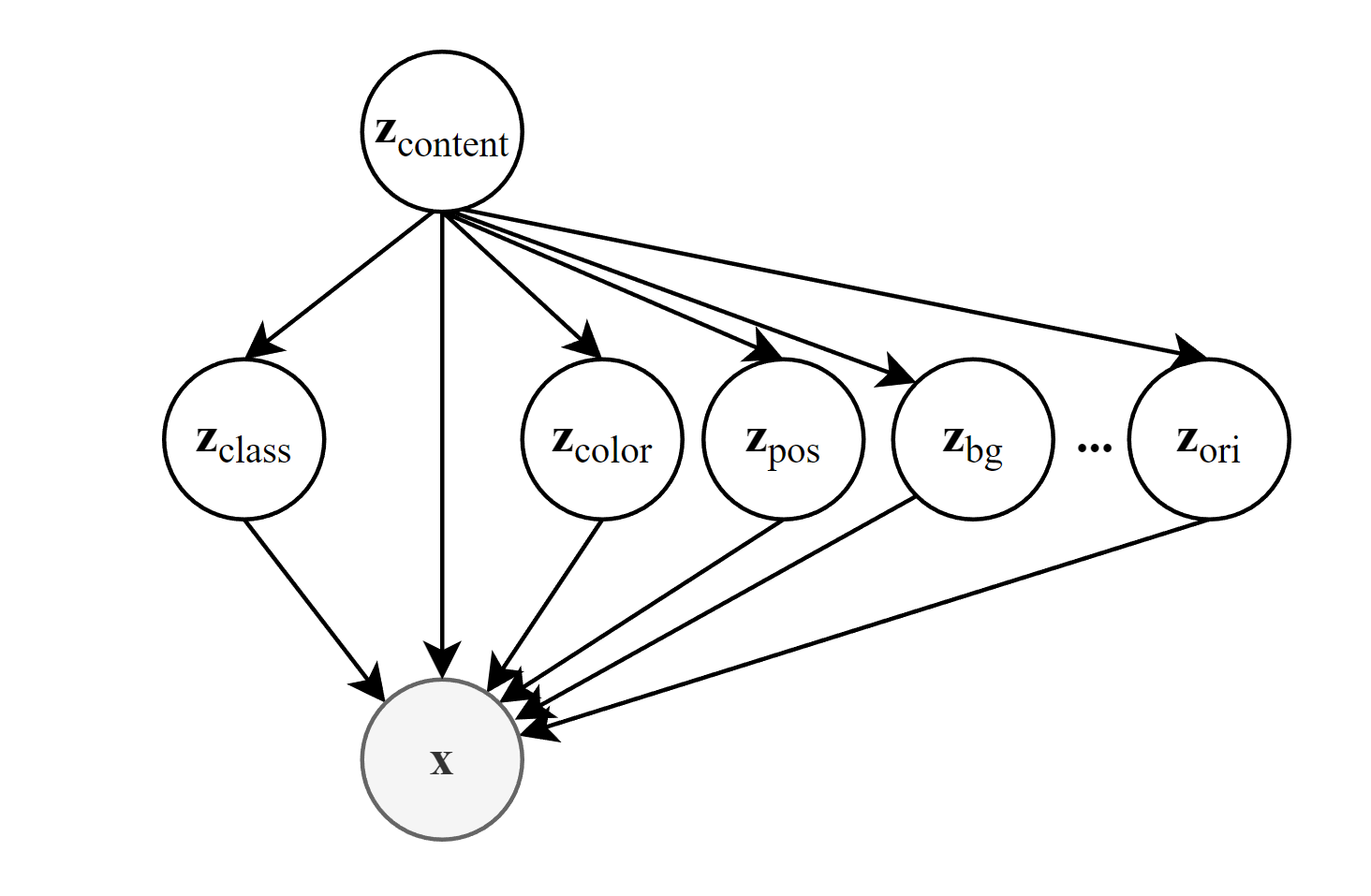

Although current researches demonstrates that the content variable causes the style variables, a question arises to me regarding the interpretation of ”content”. Specifically, as shown in fig.2, does content” in these works refer to (a) the latent variable governing the class name of a sample, causing other latent variables governing properties like color, position, background, etc., or (b) an intrinsic latent variable that is a common cause of other properties, including the class name?The distinction between these two interpretations is substantial, and it appears to be a pivotal for understanding disentaglement by contrastive representation learning – The literature says that representations of two positve samples should be mapped to nearby features, and thus be mostly invariant to not needed noise factors [4]. However, from a causal perspective, I posit that the invariance to specific noise factors (i.e., latent variables) is not determined by whether the noise factors are ”needed” for a task, but rather by the underlying causal relationship between latent variables, which constrains how one constructs the learning objective.

Now, let’s consider the two assumed situations: If the former data-generation process (a) is correct, for a classification task, one would only need to impose changes to retain class-level information, as other factors are considered noise for this task. In this scenario, positive pairs would simply need to share the same class name, while data with different class names should be considered negative counterparts. However, the effectiveness of such representations in achieving supreme robustness and accuracy in classification tasks may be limited. While this approach might work well for images containing only one class of large-scaled objects, as seen in synthetic datasets like 3DIdent and its variations, it may not be suitable for real-world images with complex backgrounds, multiple objects of different classes, and sometimes small-scaled target objects. Looking at supervised classification methods, although they do not follow a contrastive-learning protocol, their learning objectives also emphasize class-level information by treating samples with the same class name as positive samples. However, these methods often face out-of-distribution (OOD) issues, suggesting that the generative process (a) may not be appropriate, and positive pairs sharing the same class name might not be sufficient to obtain disentangled representations, regardless of the changes imposed on the data.

Discussion 1. The varied versions of 3DIdent datasets (i.e., 3DIdent, Causal3DIdent, Multimodal3DIdent) may be insufficient to verify if the intrinsic content variable is disentangled, as they lack inner-class variations of objects. In these datasets, all the samples sharing the same class name should be considered as the same object, as long as we one agree that traditional augmentation techniques (color distortion, rotation, crop, etc.) does not alter the object identity. Yet, defining ”the same object” in data is not straightforward, as some works regard different views augmented from a same sample by ”texture randomization” as a positive pair [5] – This perspective contrasts with the intuition that topology and shape determine a coarse-grained class of objects, while additional texture information defines object identity (or a fine-grained class of objects).

On the contrary, if the latter data-generation process (b) is more appropriate, changes need to be imposed on data without altering the fact that the target objects in a positive pair should be the same instances, i.e., maintaining object identity. In this context, the answer to the question illustrated in fig. 1 would be that two images with different bicycles should not be considered a positive pair, nor should the two text prompts. This perspective explains this disconcert: considering a positive pair like ”a dog in a sketch” and ”a photo of a yellow dog,” this prompt pair cannot constrain the dog as the same identity (similar shape) in the two prompts. Consequently, only to disentangle the variable governing the class name by aligning the samples with the same class names is unachievable due to the unresolved dependence on \(\mathbf{z}_{class}\) variable and other latent variables without modeling the true content variable.

Xiao et al., 2020 [5] argue that current methods introduce inductive bias by encouraging neural networks to be less sensitive to information regarding augmentation, which may help or hurt. However, I believe that this “hurt” is attributed to the insufficient disentanglement of the latent content variable due to limited changes. Upon the (asymptotical) disentanglement of the intrinsic content, the resulting representations should distributed on hypersphere \(\mathcal{S}^{n-1}\) in a n-dimensional space according to the common assumption of data manifold in contrastive learning literature. Therefore, the representations could be applied to instance identification with clustering by spherical distance on this hypersphere, and with the linear separablility of the representations, other downstream tasks (relating to one or several properties of a sample, such as classification, action detection, etc.) can be realized with linear combinations of disentangled representations. This can be regarded as the projection of hypersphere along one or several bases/axis to a lower-dimensional hypersphere (\(\mathcal{S}^{n-m}\)).

To clarify the goal of disentangled representation learning, it becomes imperative to ensure that samples of a positive pair share the same indentity, and enough changes are imposed between the negative counterparts. Yet, current methods in contrastive representation learning literature faces challenges on one or both of the two aspects for real-world data:

- Different augmented views of an image (e.g., SimCLR, BYOL, etc.) are considered suitable positive pairs for isolating the content. However, the combination of the traditional data augmentation methods are not sufficient to impose enough changes on data to cast aside all the style information.

- Employing only augmented text pairs makes it easy to impose (some aspects of) style changes on data due to the semantic and logical nature of text.However, class names in a prompt provide only the class-level constraint on positive samples, making it challenging to determine the identity of an instance solely using text data.

- Contrastive language-image training (e.g., CLIP) uses Image-text pairs, where the both parts of a image-text pair can be considered two different views of one sample, if the caption of the image is detailed, e.g. in fig. 3. However, using only image-text pairs may not be capable for disentangling the intrinsic content, as text data lacks the informativeness needed to precisely constrain the sample identity in its imagery counterpart. For instance, even if one adds numerous attributive adjectives to an object in the textual modality (e.g. “dog”), the text cannot be constrained to represent only the exact same dog as shown in the image.

Therefore, there might be a need to develop a method that combines the logic and semantic nature of textual modality with the informative nature of image modality. Text data is inherently more recaptitulative (in a property-wise manner) than image data, while image data is more precise than text data in describing “the exact same object(s)/event(s)” due to its greater informativeness than text data (per image vs.per text prompt, not per memory byte).

Reference

[1] Daunhawer, I., Bizeul, A., Palumbo, E., Marx, A., and Vogt, J. E. (2022). Identifiability results for multimodal contrastive learning. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations.

[2] Eastwood, C., von K ̈ugelgen, J., Ericsson, L., Bouchacourt, D., Vincent, P., Ibrahim, M., and Sch ̈olkopf, B. (2023). Self-supervised disentanglement by leveraging structure in data augmentations. In Causal Representation Learning Workshop at NeurIPS 2023.

[3] Von K ̈ugelgen, J., Sharma, Y., Gresele, L., Brendel, W., Sch ̈olkopf, B., Besserve, M., and Locatello, F. (2021). Self-supervised learning with data augmentations provably isolates content from style. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:16451–16467.

[4] Wang, T. and Isola, P. (2020). Understanding contrastive representation learning through alignment and uniformity on the hypersphere. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 9929–9939. PMLR.

[5] Xiao, T., Wang, X., Efros, A. A., and Darrell, T. (2020). What should not be contrastive in contrastive learning. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[6] Zimmermann, R. S., Sharma, Y., Schneider, S., Bethge, M., and Brendel, W. (2021). Contrastive learning inverts the data generating process. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 12979 12990. PMLR.