The Generalization–Specialization Dilemma

“Virtue is the golden mean between two extremes.” — Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

A self-driving car can handle routine highway driving flawlessly but struggles with unexpected edge cases. A human driver can adapt quickly but is prone to fatigue and inconsistency. Intelligence is not just about skill—it’s about tradeoffs.

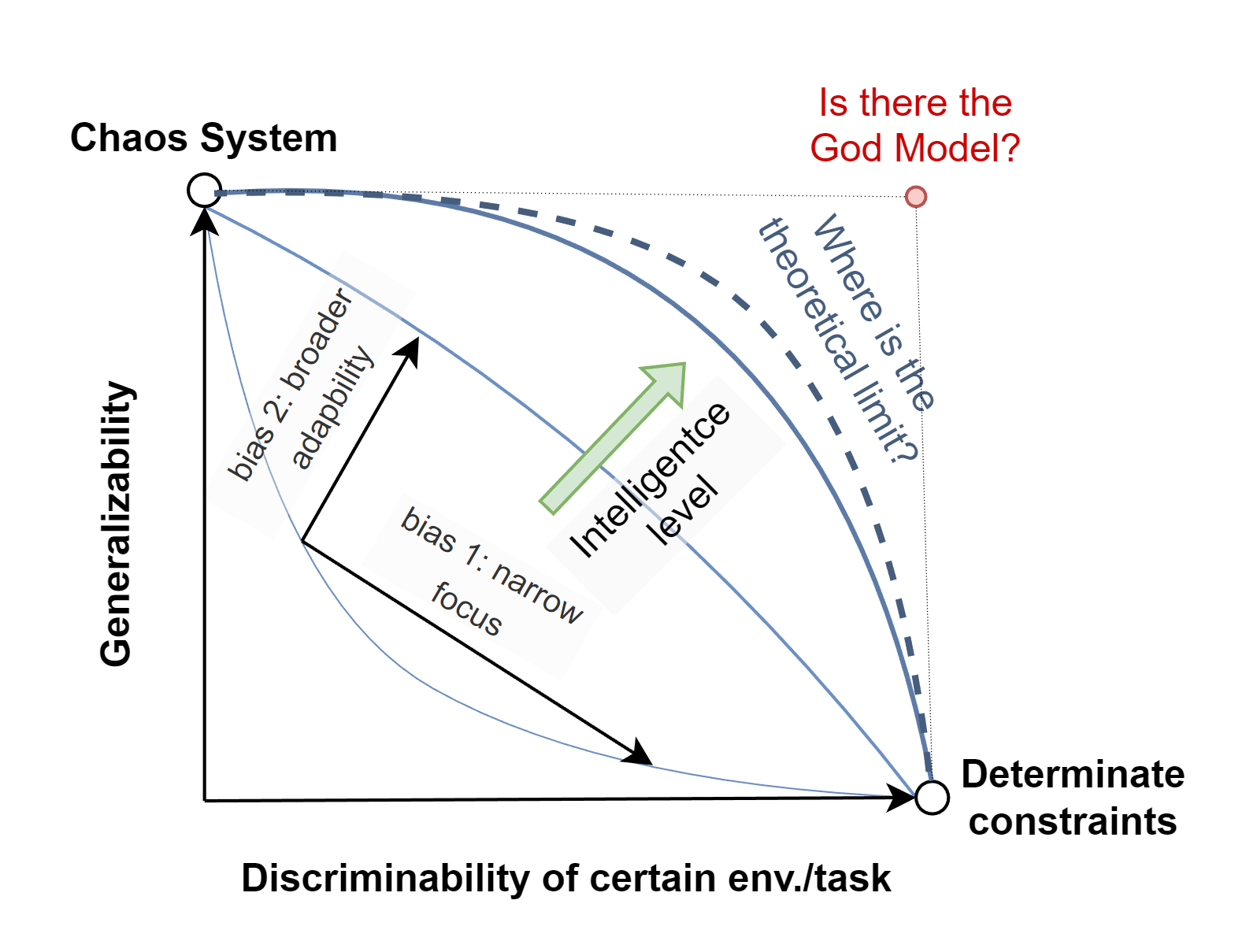

Intelligence, whether artificial or biological, faces a fundamental dilemma: the need to balance general adaptability with precise specialization. This dilemma shapes how cognitive and computational systems evolve, influencing their strengths and limitations. On one hand, an intelligence system that is highly generalizable can adapt across diverse tasks and environments. On the other hand, a system endowed with strong discriminative power excels at making precise, optimized decisions within a specialized domain. Yet these capabilities often exist in a delicate balance: placing too much emphasis on one tends to compromise the other.

This tradeoff arises not from incidental design choices but from fundamental constraints in learning and computation. Every intelligence system, whether in nature or engineered, must operate under limited resources—biology contends with energy expenditure and neuron density, while AI systems face finite processing power, memory, and data. Optimizing extensively for one end of the spectrum—say, broad adaptability—can siphon resources away from the specific optimizations needed for peak performance in a narrow field. A system designed for wide-ranging competence may thus lose some of the efficiency that a specialist would enjoy. Conversely, a domain-focused system, such as AlphaFold (remarkable at protein folding) or DeepBlue (expert at chess), achieves extraordinary precision in its niche but cannot transfer those skills to tasks that lie beyond its specialized purview.

Both natural and artificial intelligence illustrate this fundamental tension. A human polymath—like Leonardo da Vinci—can comprehend many fields but may not achieve the laser-focused expertise of a dedicated physicist who has devoted a lifetime to a single discipline. Similarly, a convolutional neural network (CNN) is superb at detecting visual patterns yet struggles with more abstract or multi-domain reasoning. By contrast, a large language model (LLM) such as GPT-4 or DeepSeek can address a broad array of tasks with surprising deftness but often lacks the exactitude required for specialized domains like advanced theorem proving or intricate strategic planning. Meanwhile, evolution has likewise shaped creatures around this same principle: an owl’s vision is optimized for darkness but less effective in daylight, and a dolphin’s echolocation is a specialized marvel underwater yet does not extend its utility to terrestrial environments.

At its core, this tension highlights that the more an intelligence system generalizes, the less precisely tuned it may be for any particular domain—and the more specialized a system becomes, the less it can smoothly transfer its knowledge to new settings. From here arises a fascinating question: Is this tradeoff an inescapable fact of intelligence, or might a sufficiently advanced system—biological or artificial—eventually transcend it?

Some have speculated about a “God Model,” an idealized intelligence possessing both maximal breadth of adaptability and maximal domain-specific precision, thus challenging the very constraints that define cognitive systems as we understand them today. While theoretically conceivable, the sheer computational and algorithmic complexity required to balance both extremes remains an unsolved challenge. Whether such a model can ever exist, or whether intelligence will always be confined by the need to balance generalization and specialization, remains an open debate. For now, this tradeoff remains a fundamental principle shaping our understanding of both minds and machines.

Bias: The Engine of Intelligence

If intelligence is inherently constrained by this tradeoff, then what drives its ability to function effectively within these limitations? The answer lies in bias—often misunderstood as a flaw, but in reality, the structuring force behind cognition. Intelligence—whether biological or artificial—does not emerge in a vacuum. It requires organizing principles to prioritize relevant information, structure knowledge, and guide decision-making. Bias is what enables intelligence to extract structure from chaos—without it, cognition would be directionless, lost in an overwhelming sea of possibilities. The very act of recognizing or learning any pattern depends on having some innate or acquired predisposition to highlight certain features over others.

Rather than merely constraining intelligence, bias drives cognition and learning. It determines how well a system can adapt broadly (generalization) versus how precisely it can perform specific tasks (specialization). In biological organisms, specialized neural structures—such as the fusiform face area (FFA) in humans—enhance facial recognition speed and accuracy. Yet this specialization reduces flexibility when tackling tasks that require different cognitive architectures.

In AI, Large Language Models like GPT-4 or DeepSeek are optimized for sequential text prediction, allowing them to generate coherent language across diverse topics. However, the same architectural biases that enable this fluency limit their symbolic reasoning capabilities, restricting their ability to solve tasks beyond their core training objectives. In both cases, the strengths of bias in one domain often create blind spots in another.

These built-in biases extend beyond structure. Every intelligent system—biological or artificial—is shaped by an objective function that defines its purpose.

For instance, Large Language Models minimize next-token prediction error, producing remarkable fluency but sometimes sacrificing factual accuracy due to training data limitations. Meanwhile, Reinforcement Learning agents optimize for reward maximization, which can lead to unexpected or exploitative behaviors if incentives are misaligned with broader human values. Evolution offers a biological parallel—survival and reproduction shape cognitive skills, but not necessarily in ways that prioritize rationality or universal accuracy.

Bias also arises from the data that intelligence systems consume. Neither biological creatures nor AI models have direct access to unfiltered reality. The human brain processes only a narrow slice of the electromagnetic spectrum, while other species perceive sensory inputs humans cannot detect.

Memory, too, is far from a perfect recording device—it reconstructs rather than stores information, introducing distortions. Similarly, AI models learn from curated datasets that carry cultural, historical, and linguistic biases. Even hardware sensors—cameras, microphones, and gauges—are designed by humans to capture specific information, filtering out vast portions of reality. Thus, every intelligence—biological or synthetic—operates within a biased lens, constrained by its perceptual and computational limitations.

Although bias might seem like an obstacle, it is also what enables intelligence to function efficiently. A system without inductive biases—no assumptions about the world—would be paralyzed by too many possible interpretations.

Neural networks need structured weights and architectures to begin learning. Similarly, human infants are born with innate cognitive templates that accelerate language acquisition and face recognition. These predispositions act as catalysts, allowing both biological and artificial intelligence to scale up in complexity rather than starting from scratch.

Bias, then, is the mechanism that balances generalization and specialization. Some biases push toward broad adaptability, while others enhance domain-specific precision. Without such constraints, intelligence would lack structure, failing to develop meaningful expertise in any area. Even if a sufficiently advanced intelligence could theoretically reconfigure its biases, Gödel’s incompleteness theorem suggests that within any sufficiently powerful system, there will always be unprovable truths—hinting that some tradeoffs may be inescapable.

This dual nature of bias—as both an enabler and a limitation—raises a profound question: Can intelligence ever reconfigure its own biases? Could an advanced AI modify its own architecture and objectives to escape the tradeoffs imposed by its design? If “reconfigurable bias” is possible, then a sufficiently advanced system might transcend its original constraints. But if biases are always embedded at a foundational level—from data limitations to hardware constraints—then even the most sophisticated AI will remain bounded by structural limits, much like biological intelligence.

This tension connects back to the “God Model” hypothesis—the idea that intelligence might one day break free from its inherent tradeoffs. But it also aligns with dialectical perspectives, suggesting that tradeoffs are not flaws but fundamental structures in learning and cognition.

Monism vs. Dialectics: Philosophical Views on Intelligence

At the core of this debate lies a fundamental question: Is intelligence a unified essence that can one day achieve both perfect generalization and specialization (Monism), or is it an evolving interplay of contradictions that will always be bound by tradeoffs (Dialectics)?

-

Monism envisions intelligence as convergent—advancements in computation, architecture, and self-modification could eventually overcome tradeoffs. Thinkers like Kurzweil argue that AI may reach a point of recursive self-improvement, leading to a “God Model” capable of both broad adaptability and expert precision. This view aligns with Platonism and the Singularity Hypothesis, suggesting intelligence is moving toward an ideal state.

-

Dialectics, on the other hand, holds that intelligence emerges through competing demands rather than transcending them. Just as biological cognition evolved under conflicting pressures, artificial intelligence may always face tradeoffs. The No Free Lunch Theorem (NFL) reinforces this view—no system can be optimal for all tasks, meaning intelligence is shaped by unavoidable structural constraints.

This debate has practical implications for AI development. If intelligence is fundamentally constrained by tradeoffs, then attempts to optimize AI systems must acknowledge these limitations. However, if intelligence can eventually reconfigure its own constraints, then AI research may one day produce systems that balance generalization and specialization in unprecedented ways. The answer may not be absolute. While NFL suggests a universal best model is impossible, real-world domains are often structured rather than arbitrary. Could intelligence find semi-universal patterns that reduce tradeoffs in practice?

Personally, I find myself leaning toward the dialectical view—Perhaps intelligence is not about resolving tradeoffs but about navigating them. In that sense, the evolution of intelligence—biological or artificial—may not be a journey toward an ideal state, but an endless process of reshaping its own limits.

AI Approaches to Reducing the Tradeoff

While these philosophical perspectives frame our understanding, AI research offers practical strategies to mitigate—though not entirely resolve—this fundamental tension. In the context of the monism vs. dialectics debate, these techniques can be seen as either incremental progress within existing constraints (a dialectical view) or potential steps toward an intelligence that may one day transcend them (a monistic view).

One such approach is Mixture of Experts (MoE), where tasks are distributed across specialized subnetworks that activate dynamically. This allows models like Google’s Switch Transformer and DeepSeek to improve efficiency while maintaining flexibility, though they remain constrained by predefined structures. Another strategy is meta-learning (“learning to learn”), which trains models to adapt quickly to new tasks with minimal data. Techniques like MAML enable neural networks to generalize across domains while retaining the ability to specialize when needed. However, meta-learning still requires a balance between prior knowledge and adaptability. A third approach, self-supervised learning (SSL), builds broad representations from unlabeled data, powering models like GPT-4 and CLIP. While SSL enhances generalization, domain-specific fine-tuning is often needed for precise tasks, reinforcing the tradeoff’s persistence.

Despite these advances, no method fully eliminates the inherent tension. A promising direction might be integrating meta-learning with a dynamic MoE framework, allowing models to not only specialize but also adapt in real-time, drawing on shared global knowledge. Yet, if even the most sophisticated architectures cannot escape this tradeoff, it raises a deeper question: Is intelligence fundamentally constrained?

The existence of these partial solutions suggests that AI may continue evolving within a dialectical framework, constantly balancing opposing forces rather than achieving a perfect synthesis of generalization and specialization. However, it remains an open question whether future architectures—perhaps leveraging neuromorphic computing, quantum processing, or new forms of abstraction—will eventually push these limitations to an unprecedented frontier, fundamentally altering our understanding of intelligence.

References

Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, et al. Gpt-4 technical report[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. 1976.

Fedus W, Zoph B, Shazeer N. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity[J]. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2022, 23(120): 1-39.

Finn C, Abbeel P, Levine S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks[C]//International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2017: 1126-1135.

Fodor J A. The modularity of mind[M]. MIT press, 1983.

Geman S, Bienenstock E, Doursat R. Neural networks and the bias/variance dilemma[J]. Neural computation, 1992, 4(1): 1-58.

Jacobs R A, Jordan M I, Nowlan S J, et al. Adaptive mixtures of local experts[J]. Neural computation, 1991, 3(1): 79-87.

Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold[J]. nature, 2021, 596(7873): 583-589.

Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow[M]. macmillan, 2011.

Kurzweil R. The singularity is near[M]//Ethics and emerging technologies. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005: 393-406.

Liu A, Feng B, Xue B, et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437, 2024.

Mitchell T M. The need for biases in learning generalizations[J]. 1980.

Wolpert D H. The lack of a priori distinctions between learning algorithms[J]. Neural computation, 1996, 8(7): 1341-1390.

Wolpert D H, Macready W G. No free lunch theorems for optimization[J]. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation, 1997, 1(1): 67-82.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Cai, Yichao (Feb 2025). The Generalization–Specialization Dilemma. https://yichaocai1.github.io.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{cai2025the-generalization-specialization-dilemma,

title = {The Generalization–Specialization Dilemma},

author = {Cai, Yichao},

year = {2025},

month = {Feb},

url = {https://yichaocai1.github.io/blog/2025/The-Generalization-Specialization-Dilemma/}

}